Cognitive Biases in Creative Output

We don't have the best intuitions when it comes to creative output. We need to be more mindful of our task switching bias.

We don't have the best intuitions when it comes to creative output.

This is especially true of the classic mode of thinking associated with creativity - divergent thinking - where you're tasked with generating many solutions to an open-ended problem.

A recent study found that the majority of participants incorrectly predicted the best strategy for divergent thinking. Given two open-ended tasks, they assumed that approaching them one at a time would be more effective than continually switching. In fact, the results showed the exact opposite.

This is a cognitive bias that we need to be more mindful of - let's call it task switching bias.

It makes sense that people are wary of task switching. You constantly find yourself switching between tasks in life and makes it difficult to get anything done. When it comes to divergent thinking, however, task switching is actually really helpful. Why is that?

The wrong way to approach open-ended problems

Let's imagine a classic open-ended problem that we often deal with.

Picture this - a friend's birthday is coming up very soon and you're not sure what to get them. You sit down and give yourself 5 minutes to come up with as many ideas as possible, good or bad. What might this look like?

You first get the common ideas out of the way - a gift card, a book, a nice bottle of liquor. Then you think about the person's interests. Let's say they love cooking, so you think about getting them a cookbook or that outdoor pizza oven you keep seeing ads for.

What else? This is usually the point where people are stumped and don't know how to move forward. After the first few ideas, it becomes harder and harder to think of something new because of cognitive fixation. People become stuck on a certain frame of thinking about the problem (e.g. cooking), and have a hard time imagining a different route. You know that there are plenty of other great gift ideas, but your mind keeps thinking of cooking-based gifts. How do you break out of this context?

You can think of the solution space of possible gift ideas as a tree, where ideas (fruits) on the same branch are more closely related than ideas on different branches.

Cognitive fixation is simply getting stuck on one branch of the tree, where all the fruits are related to cooking. But once you exhaust all the good ideas on the cooking branch, you need to move on to another area where there are still many good ideas. The question is, how do we get to all the other fruits on the tree?

If we knew exactly where to find the other fruits or how to get to them, this wouldn't be a problem. You can't simply move to another branch mentally, you need some entry point. For example, you landed on the cooking branch by thinking about your friend's interests. Similarly, you need entry points to access the other branches.

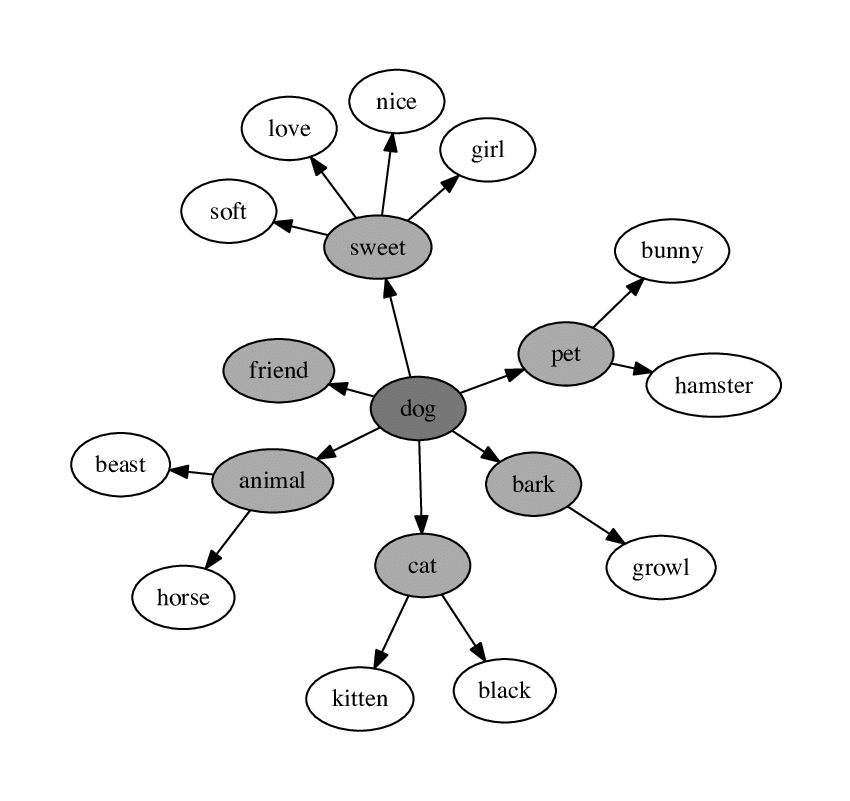

Scientifically, this is formalized as the spreading activation theory. For example, thinking of a dog (entry point) activates semantically related concepts (e.g. pet, sweet) which in turn activate other concepts (e.g. bunny, nice).

With this in mind, it seems clear that dwelling on a divergent thinking task for too long is less then ideal. We get stuck on one metaphorical branch of related ideas that reinforce themselves by spreading activation, causing cognitive fixation. Ideas on other branches are actively inhibited when we are fixated.

Many people intuitively discover that sitting down and coming up with tons of gift ideas doesn't work. Instead, we often have the question in the back of our minds over the course of weeks and take note of ideas as them come up.

The advantage here is that you find yourself in many different contexts over time - your house, your work, window shopping as you're going somewhere. Each one of these situations activates different branches of your metaphorical tree. Gift ideas that are semantically related to these contexts are more easily accessible.

By spending time in different contexts, you're increasing the amount of possible entry points you have. The entry points can come from anywhere, from your immediate surroundings to things on your mind from conversations with others.

But we don't always have these luxuries. How might we artificially manufacture different contexts to more effectively explore the solution space? In other words, how might we maximize the number of metaphorical branches of related ideas we activate?

Strategies for better creative output

Taking a break is common strategy that frees people from their fixated mindset by reducing the recency of stagnant ideas. That's great, but it doesn't really help as far as priming new contexts.

In the world of UX design, it's very common for designers to approach a new problem by taking inspiration from what's already out there. By scrolling through a site like Dribbble, they are exposing themselves to a variety of contexts that might be helpful. Unfortunately, there is rarely a repository of ideas relevant to your problem like in design.

Design thinking is a framework for creative problem solving that's fairly common these days. During brainstorming sessions, the facilitator usually comes prepared with a number of "trigger questions" that are designed to put the participants in a different mindset.

Let's say we're trying to design a wallet. Here are some example trigger questions:

- What if you were designing for someone that only uses cash? No cash?

- What if it was a luxury wallet that people paid $1,000 for?

- What if you were designing a wallet for kids?

Each of these questions takes you to a different part of your metaphorical tree and lets you explore what's possible. While not all of them would actually be relevant for the eventual solution, having a large quantity of ideas to begin with is more likely to generate an insightful feature or design.

When you're faced with an open-ended problem, like finding a gift for a friend, challenge yourself to think in different contexts via trigger questions. Every time you feel yourself slowing down with one question, move on to the next. This way, you're never fixating on any given branch for too long.

Friday Brainstorm Newsletter

For more, join 300+ curious people subscribed to the Friday Brainstorm newsletter. It’s one email a month with the most interesting ideas I've found related to science and health.